The “Tree of Life” is synonymous with evolution theory; the concept can be traced back to ancient Egyptian mythology, the Bible’s Genesis and is even harnessed by Charles Darwin in support of natural selection. The earliest scholars have worked to depict the relationships between plants and animals and how to convey the adaptive and semi-random splits and changes in their respective lineages since 3000 B.C.

In researchers’ continual quest to understand the present by tracing our past, the technology and methods they’re using have evolved, along with the understanding of our origins.

In the study of biological diversification, systematics — the track of biology that deals with classifying organisms — has undergone a revolution due to technological advances that make it possible, and affordable, for scientists to study the full genetic makeup of an organism.

In phylogenomic studies, the use of genome-wide datasets is rising in popularity, among systematics, as well as comparative studies, as a way of determining an organism’s genetic make-up and lineage.

However, at this intersection of evolution and genomics research, findings can often support contrasting results. And any misbalance in the samples or misidentification of a species can jeopardize the validity of a study.

Mark Sabaj, PhD, is the interim curator of fishes at the Academy of Natural Sciences and a co-author of a recently published Evolution paper entitled “Phylogenomic incongruence, hypothesis testing, and taxonomic sampling: The monophyly of characiform fishes.” In it he demonstrates the benefits of collaboration between the new-age molecular and traditional systematists when it comes to accurately identifying common ancestors.

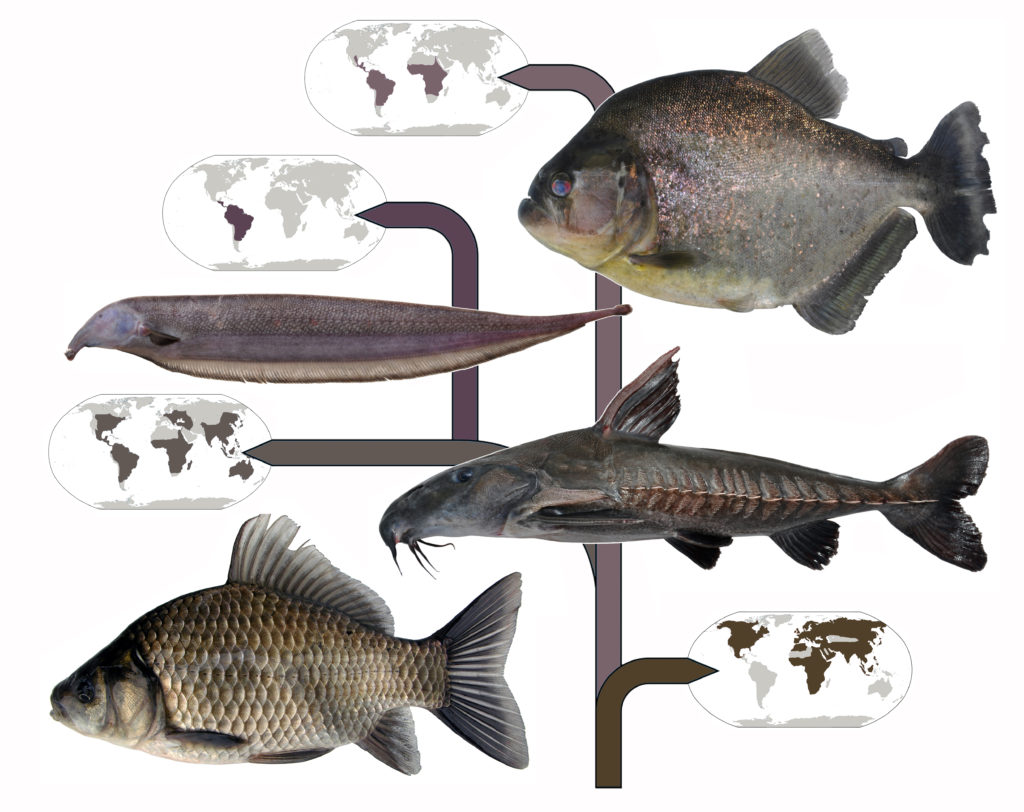

The study looks specifically at characiform fish, commonly called Tetras, which is the largest group of freshwater fishes. The group includes the tiny neon variety that are aquarium favorites; dogtooths and dorados, popular in sport fishing; the human-toothed pacus; and the menacing piranhas. Strikingly, the study firmly establishes that this diverse group of fish actually share a single common ancestor.

“Contrary to what most phylogenomic studies assume these days — that gene sampling is more important than taxonomic coverage for addressing hard-to-resolve phylogenetic problems —our results show (at least for this clade) that a good taxonomic sampling can provide more statistical power than gene sampling,” said lead author, Ricardo Betancur-R. “Recently, some authors suggested that not all tetras were closely related. But our study supports the original hypothesis that they are. We also used ‘phylogenomics’ to answer this question… a relatively new technique that looks at the whole genome, instead of a just a few genes.”

Sabaj explained that, in a general sense, the study shows that dense taxon sampling (a research method rooted in traditional systematics) is more important than analyzing a larger number of genes from fewer samples when it comes to resolving conflicting hypotheses on evolutionary relationships.

In Sabaj’s experience, only analysis of a large number of genes and dense taxon sampling could accurately test hypothesis on relationships among characiformes, because it is an extremely diverse group with a complex history spanning freshwaters on three continents in the Old (Africa) and New (North and South America) Worlds.

“Where traditionally there has been a rift between the old and the new, a combination of both methods has allowed us to draw stronger conclusions. It’s these collaborations that are producing the most reliable branches on the tree of life,” said Sabaj.

By Emily Storz

This post was originally posted at the Drexel News Blog.